Written by alarminglytired

TW: Mention of self-harm

“A face only a mother could love.” It’s a phrase I’ve come across countless times in the digital realm, used to describe someone so unappealing that only a mother’s heart could harbor any affection for them. I’ve never truly grasped this idiom in its entirety, perhaps because my reality has always felt like a warped reflection of it. I cannot fathom a reality where my mother would see beauty in me, let alone love my image.

My mother often revisits the topic of my features, dissecting them with such a peculiar blend of affection and scrutiny that you would think it’s not her own daughter’s face she is seeing. She describes my eyebrows as little nesting caterpillars, yet she despairs over how they seem to have exploded all over my face. To “x” this, she used to drag me to my aunt’s house once a month, outside the city, for what she called “taming the pests.” It was short-lived, however, as the pests would always come back in a fortnight—much to my mother’s dismay.

Then there’s my nose. It reminds her of a clown’s—too big, too pronounced. When I was young, she loved to tease me by making exaggerated gestures about how I would somehow inhale all the oxygen in the world and then she would die, and it would be my fault. Haha, mom. Hilarious. She encouraged me to spend my time pinching the bridge of my nose instead of wasting my time playing with my stuffed Mickey Mouse toy, insisting it would train my features to become more delicate, more acceptable.

My cheeks, she often exclaims, are cute and chubby, yet she laments how they dominate my face.

The only thing she loves about me are my eyes, because they are hers. She has praised how my eyes are just the right size to be adored, to be perfect—like hers. But disdain fills her when my eyes get lost in the vast expanse of my face. She used to cover my entire face with her hand and would often joke that I took up too much space. More than once, she would also mention my cousin’s smaller, supposedly model-worthy face, all the while circling back to mine and emphasizing how disproportionate it was.

I’ve quickly learned that the most beautiful things about me are tainted with an underlying current of inadequacy. That in the rare times people tell me I am pretty, it is to be swiftly followed with a “but” that makes me wonder if I am even pretty at all.

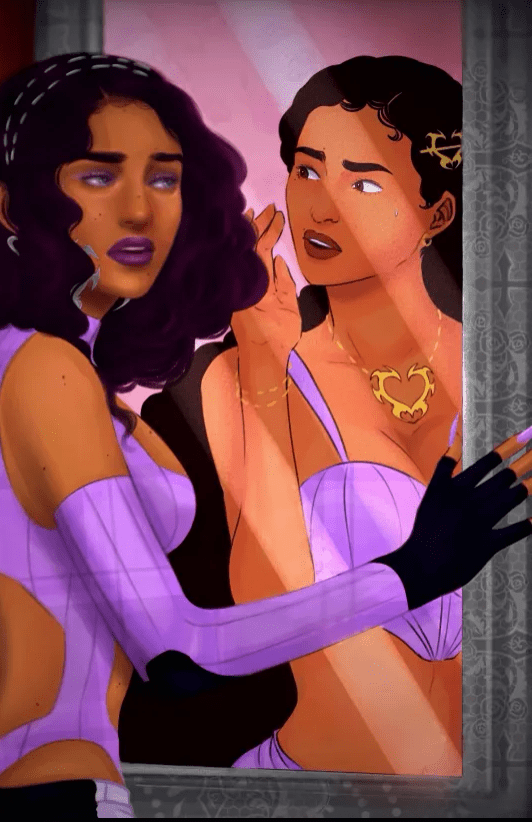

Whenever we would pass by a mirror in a mall, her comments would resurface like old wounds. She, as always, would comment about how much I look like my father. My heart would race with indignation as I would insist that it is her face I share. How could she compare my face to the man who left us, the man whose actions shattered her, who almost made her cross those pearly gates? Which always made the outrage morph into sadness, because if she thinks I resemble him, she must also think I embody the ugliness festering inside his body. I am a reflection of the hurt she so desperately wishes to escape after so many years. Each time I tape my cheeks back, hold my nose at an awkward angle, or scratch my face to try to get rid of the flaws, I’m reminded that no matter how hard I try to deny it, to mask it, I am my father’s mirror image. His blood runs through my veins, and no matter how much I bleed out on the cold bathroom floor, a simple truth has marred my entire existence: I am an unintentional portrait of my mother’s pain, a canvas painted with strokes of disappointment. And as I stare into the mirror in our shared bathroom with the lights flickering in and out, I wonder—how could anyone love a face like mine?

Discover more from SeaGlass Literary

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.