By Holly Wilcox Routledge

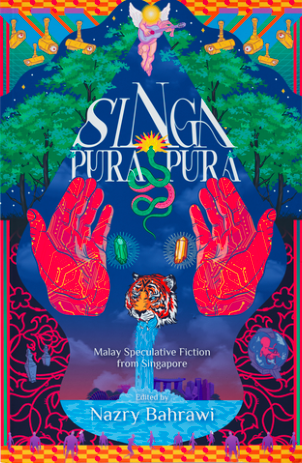

In a literary landscape dominated by anglophone speculative fiction, both at home and abroad, Nazry Bahrawi’s Singa-Pura-Pura brings Malay speculative fiction into the spotlight with a collection of thirteen short stories, each bringing a uniquely Malay angle. Faisal Tehrani gives a short but effective introduction to Singapore’s literary scene to lay the ground for the first short story, ‘Beginning’ by nor, which is a retelling of the Islamic creation story, whilst Bahrawi further pushes the idea on what can be considered spec-fic, and where Malay authors and their work fit within the genre, in an afterward essay, ‘Malay Speculating Futures’.

The anthology organises the thirteen short stories into four separate sections, each accommodating the usual themes present within speculative fiction: science fiction and technology; urban fantasy and horror; fantastical realism that leans heavily on the fantastic; and a section dedicated towards the examination of the familial unit, or any kind of unit, that sees how it splinters or strengthens under the weight of possibilities.

In ‘Prayers From a Guitar’, Nuraliah Norasid examines patriarchal expectations and entitlement when an ustaz contemplating taking a second wife encounters an angel playing a guitar. ‘Transgression’ by Diana Rahim takes on a modern-day retelling of a dance ritual from the east coast of Malaysia called Ulek Mayang. In the more sci-fi leaning section, ‘Doa.com’ presents an interaction between two men at a cemetery in a world where robots and AI have been implemented in everyday life, whilst ‘Quota’ focuses on a woman trying to find personal happiness in a society where humans have become able to accumulate and spend it. As for the more speculative section, in ‘Mother Techno’, a woman navigates caring for her relative and utilizing an intelligence system designed to improve human birth rates; in ‘Second Shadow’ a political writer realises he has grown a second shadow; and in ‘Tujuh’, written by Bahrawi himself, the narrative follows a series of murders over the course of Ramadan.

But it’s after the short stories end and Bahrawi returns that this compilation brings out the ultimate question. Where the short stories show what Malay spec-fic may look like, Bahrawi in the essay ‘Malay Speculating Futures’ attempts to tell us not only what it is, but what it could be as more and more attention is drawn to narratives and authors outside of the Anglosphere, not just in Singapore, but beyond. It’s a challenge that he bravely steps up to try to answer head-on, although constricted by length and time; after all, the question of what makes speculative fiction unique to any culture or nation is one that can and has produced entire texts devoted to tracing the development of national storytelling and arts.

What is speculative fiction? Bahrawi turns to Margaret Atwood, whose definition refers to works that assume ‘things could really happen, but hadn’t completely happened when the authors wrote the books’, noting that her definition results in spec-fic being a genre outside of science fiction, referring to sci-fi as ‘a genre that imagines “possible futures” rooted in the view that our current material reality could lead to such wild possibilities’. But he also turns to the poet Ng Yi-Sheng, who put forth in The Straits Times ‘that local [Singaporean] speculative fiction can be traced to the 1950 ghost stories of Othman Wok, and the Malay magazine Mastika.’ The latter observation, Bahrawi points out, means that Malays have been ahead of the curve, including before Atwood herself, since ghost stories have been an integral part of Malay culture, with some of the most well-known Malay-language films being those centered on the Pontianak.

Bahrawi’s interrogation of the sci-fi-infused spec-fic stories also prompts a deeper look into the role of technology within everyday society, whilst still holding onto the questioning framework of spec-fic. After all, if spec-fic is about things that could really happen, but haven’t already, what does it mean to write about the personalisation of AI in a time and age where AI has not only become so commonplace it is used in day-to-day situations like drafting letters, but has also prompted a massive cultural backlash? Can we truly write spec-fic about an AI that grows to become what we consider human, what with so many articles published now desperate to make us understand that AI as we know it is merely a glorified calculator regurgitating information whenever prompted, rather than the all-seeing individual that sci-fi writers, and perhaps many of us, have tried to make it out to be? And if we can consider that spec-fic, what does a distinct Malay flavour look like?

Perhaps there will never be a clear-cut answer to these questions. After all, Bahrawi poses them to question our understanding of genre, culture, language and how these interact with each other, encouraging others to interact further with the spec-fic genre. However, there is an avenue that Bahrawi, and the anthology as a whole, shines in, and it’s in its open-minded, frank presentation of Malay culture and language that pushes non-Malay audience members to engage themselves with the stories on a more personal level. Bahrawi later writes, ‘This anthology must also challenge the perception that Malay literary writing is perpetually lamenting lost places and tradition in the forms of displacement and nostalgia, though these themes are certainly present in some of the stories here.’ This statement is probably the single sign that the anthology has succeeded; Malay terms are written unitalicised and un-othered, written into conversation without any over-explanation to make a non-Malay audience feel comfortable. After the essay, in fact, is a whole glossary for each story, meaning readers can flip the pages themselves to uncover any explanation they require, instead of waiting for the writers to explain it to them.

Discover more from SeaGlass Literary

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.