Personal Essay by Gi Buelow

CW: mentions of death

Life is never what you think it is going to be.

“That’s the beauty of it,” your mom would say with a slight gleam in her eye. “The unpredictability is what makes life worth living.”

I disagree.

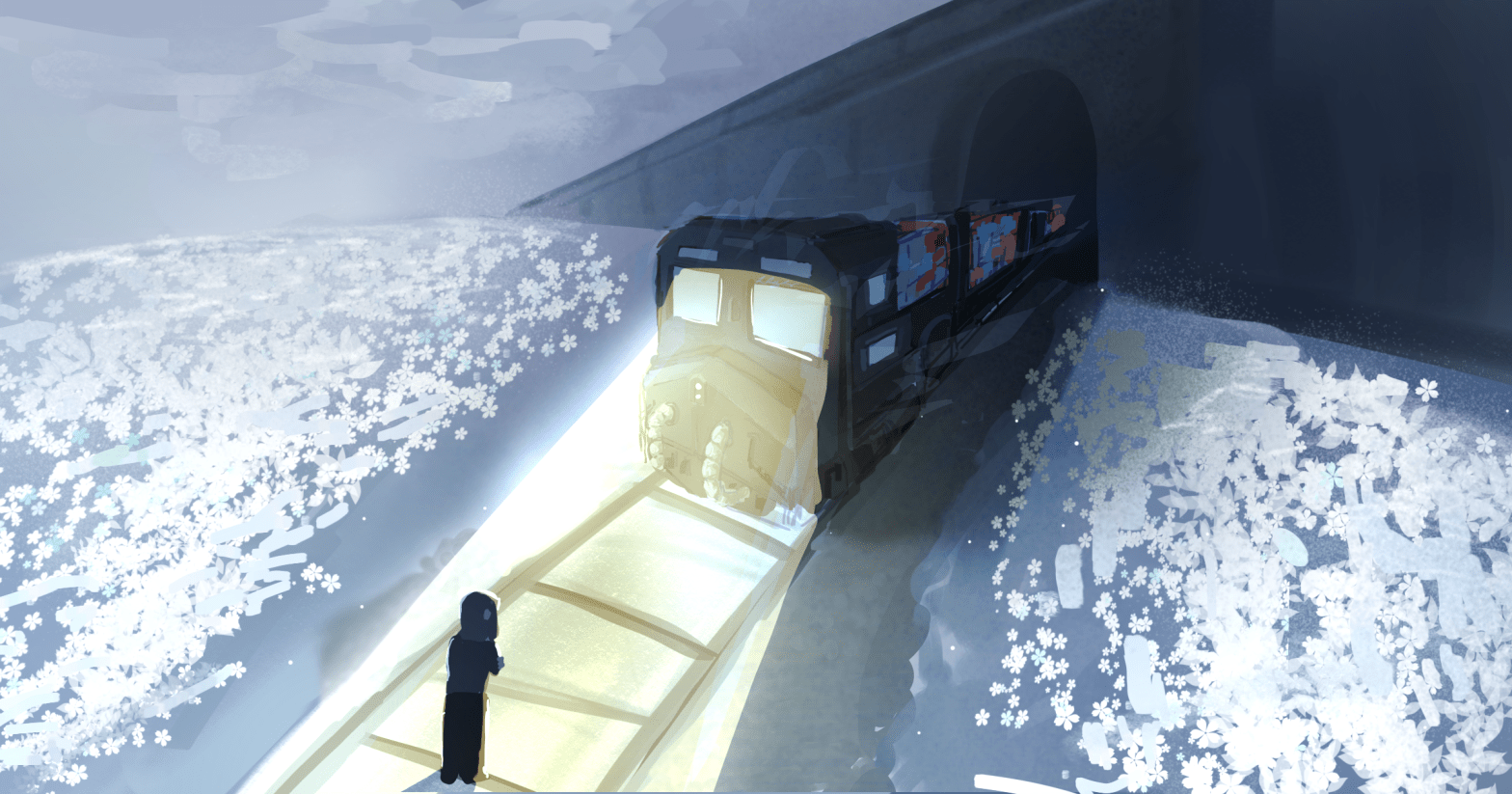

The unpredictability is harmful. It is pain. It is a freight train barreling towards you, full speed and not braking, and while you have the choice to move, you do not have the time.

One moment, you’re finishing up your last few homework assignments, and the next, you’re hugging your crying mom, who just hung up with your nana. You’re asking her, “What happened?”

She utters two words: “Grandpa’s dying.”

At first, it doesn’t hurt; you feel no pain. Maybe you’re in denial, forcing your emotions away like you always seem to do. Or perhaps you just don’t believe it; yes, he is old, but he can’t be dying, not yet. Either way, you feel guilty. Guilty for not feeling anything, guilty for not being torn apart. Guilty for the fact that his dying never seems to hit you. It doesn’t hit you while you stand there holding your mom, or while you drive to the doctor, or during the half-hour appointment, or even on the drive home. But then you get home, and suddenly, everything falls apart. Suddenly, you’re watching yourself from an outside perspective, like your own life is some sort of twisted movie. Suddenly, you’re in your room pacing, crying… alone. Your mom is gone, saying goodbye to a man you’ll never see again; she left without you. He’s leaving without you, and you don’t even get a chance to say goodbye.

He’s nothing but a memory now. A memory of when you were twelve, sitting in a classroom, listening to a teacher ask if any of the class knew someone who had fought or been involved in World War II. Telling us we should ask them about it. You know your great-grandfather fought when he was young, in his twenties you think. Excitedly, you raise your hand, say, “My grandpa fought in the war. I can ask him about it.”

Then there you are, a month later, far past that topic in school, but your curiosity is piqued anyway. So you ask him about it, and your grandpa smiles. He tells you about how he enlisted and was in the Navy. How he spent nights on boats, talking to his friends. How when he saw a dead man for the first time, he prayed for them.

You’re not religious, but you pray now. There’s no getting better for him anymore; he has given up, but you pray that he lasts one more day—just one more, so you can say your goodbyes. So you can hear his voice one more time, see his smile one more time, so you can spend your last moments with him memorizing the feel of his hugs. You pray for him to go somewhere happy, even though you are not sure you fully believe in it. Because there’s always a chance, and just in case it’s real, you want to help him get there.

He doesn’t live another day. You lost your chance to say goodbye because you had to stay home with your brother. He’s “too young to see that,” you were told. You will never be able to say goodbye. He’s gone. Forever. And you’re mad. Your mom got to say goodbye, your nana got to say goodbye, even your step-dad got to say goodbye; but you couldn’t. And briefly, you resent your mom for this. Your last chance to see him was taken from you, ripped from your grasp almost as quickly as water slipping through your fingers. You’re mad because when things finally started to look up, you had to lose him. You’re mad because this isn’t fair; it can’t be fair. You’re a good person. Why should you have to suffer? You’re mad because you can’t stop yourself from crying in class. Because you miss him, you’re tired, and you didn’t get to say goodbye.

But you hate being angry. You hate that your brain is constantly reminding you he’s gone. So you push it away. You tell yourself it’s not real. None of this is real; it can’t be real. He’s not gone, not truly. He can’t be.

He can’t be.

On Friday, you’ll see him. You’ll drive to the nursing home and visit him and your grandma. You’ll get a new book recommendation from him, and you’ll give him a new one as well. You’ll tell him about life and school and your brothers. He’ll tell you all the stories he’s told you a million times before, but you’ll still listen because it makes him happy. On Friday, he’ll be normal and he’ll be healthy. He’ll be alive.

Except now it’s Friday, and none of that has happened. It’s Friday, and he’s not healthy, he’s not alive, and absolutely nothing is normal. It’s Friday, and he’s still gone; he’s always been gone. His room is empty: eerily devoid of life. It’s confusing because your grandma still lives here, but without both of them, without him, it doesn’t feel the same. Nothing truly feels the same. You sit in this half-empty room, your grandma to the right of you watching The Golden Bachelor, and you remember.

You remember visiting during holidays, a second-story apartment, a seemingly never empty Fudgsicle box in the freezer, a big jar of hard candies—except not the good ones, the banana ones that no one ever liked, but they were always there—an envelope with cash during birthdays, chocolate bunnies during Easter. The little things that never seemed to matter appear so significant now and… tinted. They seem tinted with a deep shade of blue. Grief. You miss him. But you don’t feel as bad as you did before.

It’s a sort of closure, perhaps. To visit this place that is no longer his place could be all you needed—some time to say goodbye. It doesn’t feel good, but you don’t feel as bad. Maybe the shock has worn off; maybe you’re finally starting to accept the fact that life isn’t forever, that it was inevitable. And as much as it hurts, it wouldn’t have hurt any less if it had happened at any other time.

So this is how you say goodbye, with tears in your eyes, your heart in your stomach, and an odd feeling of comfort. You remind yourself that he was ready to go; he was at peace with it, so you’ll learn to be at peace with it, too. You’ll hold on to the necklace with his ashes and the desk you now have that used to be his. You’ll hold on to the memories and the moments. You’ll hold on to the love you felt when you were around him. You’ll be sure that everyone around you feels the love he gave you. You’ll hold on to all of this; you’ll teach yourself to be okay. You will be okay.

You will hold on to his legacy. The legacy that you are a part of. You will hold on to him through fudge pops, and banana candies, and books, and pinky promises, and any time World War II or the navy is mentioned, and when you think of Italy or Sicily, and in the way he loved, and in the way he made people smile. You will hold on to the pictures. You will think of him every time Halloween comes around and every time April comes as well. You will remember family parties, and visits, and helping him move into assisted living, then again into a room with extra care.

He was the first family member you were close to that you lost. So, you will have regrets, of course. Regrets about not asking more about being first generation. Regrets about not writing down his stories, because you know that as time passes, your memory of his stories will fade. Your memories of him will fade. But these regrets will teach a lesson. A lesson to hold on tight to those you love, to those who love you. A lesson to cherish every moment you have. It is painfully clear to you, that even in death you’ve still learned something from him. Perhaps that will be his legacy: the lessons you learn after his passing. You thank him for that, even if you can’t do it face to face. You love him; he loved you. Through all of this, you learned to say goodbye. And even though it is hard, it will be okay again. You will be okay again. I will be okay again.

Discover more from SeaGlass Literary

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.